A report on e-waste generation worldwide was presented by the United Nations (UN) at the World Economic Forum, in January 2019. It pointed out that the e-waste stream reached 48.5 MT (million tonnes) worldwide, in 2018, and that this figure is expected to double if no action is taken. Currently, untreated e-waste represents about 70% of the hazardous waste that ends up in landfills.

What is E-waste?

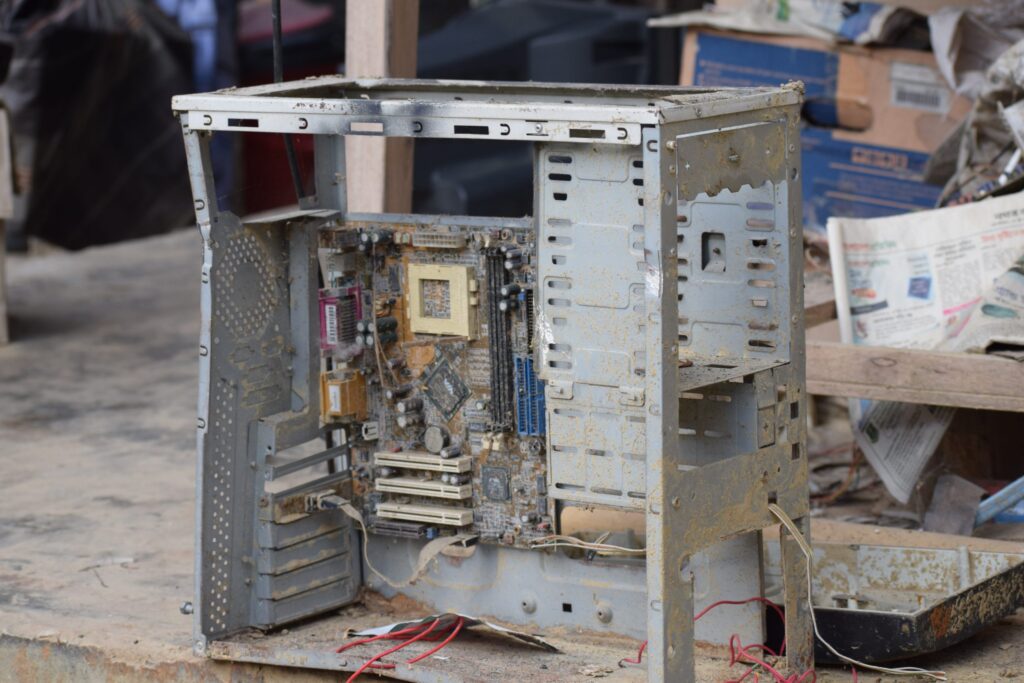

E-waste ranges from toasters to electric toothbrushes, smartphones, fridges, laptops, TVs, and anything else with a battery or electric plug. At the moment, only a handful of countries have a consistent way of measuring e-waste, however, there are no proper handling and management techniques and viable policies for the control and reduction of e-waste.

The innovation of new electronic products and the digitalization of various technologies coupled with the rapid lowering of costs has led to an increase in the production of e-waste. The problem lies in the fact that e-waste may contain precious metals such as gold, copper, and nickel as well as indium and palladium. These materials can be recovered and recycled to be used in new products and goods rather than ending up in a landfill.

According to the Global E-waste Monitor 2017, in one year, 44.7 MT of e-waste was generated. This is equal to over 6 kilograms for every person on the planet. Asia alone contributes to almost 40.7% of the total e-waste generated annually. Of this amount, a staggering 40 MT of e-waste is discarded in landfills, burned, or illegally traded and treated in sub-standard ways. Current estimates suggest that by 2021, the annual total volume of e-waste is expected to surpass 52 MT and by 2040, CO2 emissions from the production and use of electronics will reach 14% of the total emissions into the atmosphere. In the worst-case scenario, by 2050, this e-waste could top 120 MT annually.

Today, e-waste mainly consists of products like CRTs, VHS tapes, DVD players, etc. Many of these products contain toxic compounds such as lead, which are hazardous. That is why the proper disposal of e-waste products must be addressed.

Current Standards and Methodologies to Manage E-waste

The most common disposal scenarios in the world are measured by a standardised framework developed by the Partnership on Measuring ICT for Development. They state that e-waste management is usually done by the collection of e-waste in either one of the following scenarios:

Scenario 1: The Official Take-Back System

In this case, usually under the requirement of the national e-waste legislation, e-waste is collected by designated organizations, producers, and the government. This could happen through retailers, municipal collection points, and pick-up services. The final destination if the e-waste is a facility which recovers valuable materials from the waste in a sustainable way aimed at reducing the environmental impact of the waste. Once these materials are collected, the remaining waste is recycled ethically.

Scenario 2: Mixed Residual Waste

Here, consumers directly dispose of their e-waste through their normal dustbins with other types of household waste. The e-waste is then treated with the regular mixed waste from the households. Depending on the location, it can then either be sent to a landfill or a solid-waste incinerator with a low chance of separation from the mixed waste. This leads to the possibility of it negatively impacting the environment as landfilling leads to toxins leaching into the environment and incineration leads to emissions into the air. Unfortunately, this scenario currently exists in both developing and developed countries.

Scenarios 3 and 4: The Collection Outside the Official Take-Back System

These scenarios are different in developed and developing countries as their municipal waste recycling is done differently. There are two scenarios here, one for developed countries and the other for developing countries.

- Countries With Developed Waste Management

E-waste here is collected by individual waste dealers or companies and then traded through various channels. The e-waste can then be divided into metal recycling, plastic recycling, specialized e-waste recycling, and also exportation. This e-waste is not reported to the official take-back system and there is, therefore, the potential for the e-waste to not be treated in specialized recycling facilities.

- Countries With No Developed Waste Management Infrastructure

In most developing countries, there are many self-employed people who are engaged in the recycling of e-waste. They usually buy e-waste from household consumers and then sell it to be refurbished or recycled.

Once these goods are sold, they are mostly recycled through substandard recycling methods, which can cause severe damage to the environment and human health. These methods usually involve burning in the open to extract metals, acid leaching for precious metals, unprotected melting of plastics, and direct dumping of hazardous substances. The lack of good legislative measures, treatment standards, environmental protection measures, and recycling infrastructure are the main reasons for this type of recycling.

Re-evaluation of E-waste Disposal Techniques

Forecasts show that e-waste is worth $62.5 billion annually, which is more than the GDP of many countries. This means the proper disposal of e-waste is essential and a more effective use would be to give the products a second-life, which keeps materials at a higher value. Recycled materials are 2-10 times more energy-efficient than metals smelted from virgin ore. This means that by recycling the raw materials in electronic goods, we can considerably lower carbon emissions. This will form a circular economy in which waste will be designed out of the system.

To build this economy, we have to focus on designing products that are durable, reusable, and recyclable. This will ensure longer circulation of electronics, thus increasing their value. We have to also focus on urban mining which is a technology that will be able to extract metals and minerals from e-waste. More countries should adopt e-waste legislation, such as extended producer responsibility, and build a formal recycling industry. Once the product has reached its end, the materials must be collected and reintegrated into production and electronic services should help replace physical products.

A circular economy could reduce costs for consumers by 7% by 2030 and 14% by 2040. This will not only help in reducing costs but also in creating more jobs as new designers, circular economists, and urban mine specialists will be needed.

Conclusion

A transition from current e-waste management schemes to a circular economy for the proper handling of e-waste will benefit society at large. Circular economy models must be appointed to encourage closing the loop of materials through better design of components, recycling and reusing. The time to reconsider e-waste management and replace it with viable policies and actions is now.